I (Clare) love sharing good news. Our book Building Bridges: Rethinking Literacy Teacher  Education in a Digital Era has just been published. Being modest (tee hee) I think it is blockbuster!!!! Attached is a flier for the book and when you look at the Table of Contents you will see what I mean — incredible contributors. Here a flier for the book Building Bridges_Flyer

Education in a Digital Era has just been published. Being modest (tee hee) I think it is blockbuster!!!! Attached is a flier for the book and when you look at the Table of Contents you will see what I mean — incredible contributors. Here a flier for the book Building Bridges_Flyer

If you are comfortable share this info on your FB page/Twitter/Website. The tiny url is http://tinyurl.com/hwtvoua

I am so proud of this book and learned so much editing it!

Category Archives: communicating ideas and research

Why reading is good for the brain

I (Clare) found this terrific article on reading which build on World Book Day. Below is the  link and the article. So after reading the blog, relax with a tea and read a good book!

link and the article. So after reading the blog, relax with a tea and read a good book!

http://www.msn.com/en-gb/health/mindandbody/why-reading-is-good-for-the-brain/ar-AAdUrDU

If you love reading, you won’t need us to tell you how beneficial curling up  with a book can be, but studies have shown that picking up a novel has health effects that extend beyond the immediate de-stressing and pleasure it brings.

with a book can be, but studies have shown that picking up a novel has health effects that extend beyond the immediate de-stressing and pleasure it brings.

To celebrate World Book Day (March 3), we want to talk about the less obvious health benefits books can bring. Reading is time well-spent!

Reading fires up your brain

Researchers at Liverpool University revealed that reading Wordsworth, Shakespeare and other classics “lights up” the brain under scanners. However, when participants were given easier, modern translations of the books, the brain boosting effects were less, suggesting that reading trickier texts is better for you. Areas of the brain fired up included not only the left part of the brain concerned with language, but also the right hemisphere that relates to autobiographical memory and emotion.

Researchers at Liverpool University revealed that reading Wordsworth, Shakespeare and other classics “lights up” the brain under scanners. However, when participants were given easier, modern translations of the books, the brain boosting effects were less, suggesting that reading trickier texts is better for you. Areas of the brain fired up included not only the left part of the brain concerned with language, but also the right hemisphere that relates to autobiographical memory and emotion.

Effects are enduring. A study at Emory University in the US found that reading a book causes heightened connectivity in the brain and neurological changes that persist even after you’ve stopped reading.

Reading can slow the progress of Alzheimer’s

Reading can lower the levels of a brain protein involved in Alzheimer’s, researchers have  claimed. US scientists looked at beta amyloid protein levels in 65 healthy older people and compared the results with Alzheimer’s patients. They found lower levels of amyloid in the brains of people who had read, written, played games, or taken part in other cognitively stimulating activities throughout their lives.

claimed. US scientists looked at beta amyloid protein levels in 65 healthy older people and compared the results with Alzheimer’s patients. They found lower levels of amyloid in the brains of people who had read, written, played games, or taken part in other cognitively stimulating activities throughout their lives.

Lead researcher Susan Landau, of the University of California, Berkeley, said: “We report a direct association, suggesting that lifestyle factors found in individuals with high cognitive engagement may prevent or slow deposition of beta amyloid, perhaps influencing the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.”

In fact, reading slows mental decline in general

People who read books are more likely to have healthy brains in old age, according to research published in the journal, Neurology. The study looked at 294 elderly participants and found that those who had taken part in mentally stimulating activities – such as reading – had lower rates of mental decline as they got older. Conversely, those who rarely read or performed other stimulating mental activity mentally declined 48 percent faster than average.

“Our study suggests that exercising your brain by taking part in activities such as these across a person’s lifetime, from childhood through old age, is important for brain health in old age,” said study author Robert. S. Wilson of the Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Reading can improve your memory

Scientists at Liverpool University found that reading poetry stimulates activity in the brain area associated with autobiographical memory. There’s a lot to remember when you read – plot, sub-plots, characters, emotions, your own evaluation of what’s going on – and all of this effectively gives your brain a “work-out”.

Reading improves your concentration

For many of us, life is frenetic and we spend our days juggling a million jobs. If you regularly find yourself chatting online at the same time as speaking on the phone, trying to get work done and dealing with family demands then you’re not alone. However, this type of frantic multitasking has been shown to lower productivity, meaning you get less done in the long-run. The discipline of focusing for prolonged periods on reading a book is good for your powers of concentration and can have a far-reaching effect on your life.

Reading lowers stress

If you’re stressed, reading is one of the most effective, enjoyable ways of making yourself feel better. Part of this is common sense; getting lost in a book will take you away from your worries for a while, giving you new perspective when you return. However, research has found that reading lowers stress faster than other activities such as walking or listening to music. Research from the University of Sussex found that subjects only needed to read for six minutes to slow down their heart rate and ease tension in the muscles.

Reading may help with depression

Several studies have suggested that reading can help with mood disorders such as depression. A study published in the journal PLOS ONE showed that reading self-help books, alongside therapeutic support sessions, lowered depression more effectively than traditional treatments alone. Even in severe cases, reading the right kind of book can improve your mental health. According to a study at the University of Manchester, people with severe depression can also benefit from “low-intensity interventions,” such as self-help books.

Reading can help you sleep

Most sleep expert suggest that insomniacs should create a calming bedtime routine, away from phone and computer screens which can stimulate brain activity with their lights (not to mention annoying posts from distant relatives). Reading a non-stressful book under a gentle light can be part of this routine, but choose your book wisely; anything too exciting may have the reverse effect.

Reading give you better analytical skills

Reading is a complex process, involving several parts of the brain as you piece together and visually recreate what’s happening. This brain activity will stand you in good stead for becoming more widely analytical. Research at the University of Berkeley revealed that readers are able to spot patterns more quickly, a key tenet of good analytical thinking.

Reading makes you more empathic

Reading fiction makes you a nicer person. There, we’ve said it, and research will back us up. A team at the University of Toronto found that the more fiction a participant had read, the higher they scored on measures of social awareness and tests of empathy, such as being able to take another person’s perspective or being able to accurately read emotions from looking at someone’s eyes. On the other hand, people who regularly read non-fiction were found to display the opposite characteristics, making them less empathic.

Reading literally makes you cleverer

Canada’s Keith E. Stanovich, Emeritus Professor at the University of Toronto, is a world leader in the psychology of reading. Stanovich has carried out a vast amount of research into the topic and the conclusion of one meta-analysis reads: “If ‘smarter’ means having a larger vocabulary and more world knowledge in addition to the abstract reasoning skills encompassed within the concept of intelligence, as it does in most laymen’s definitions of intelligence, then reading may well make people smarter. Certainly our data demonstrate time and again that print exposure is associated with vocabulary, general knowledge, and verbal skills even after controlling for abstract reasoning abilities.”

Digital literacy conference in teacher education

I (Yiola) am excited to share news on a technology conference hosted in the Child Study and Education program at OISE/UT last week. The conference, Technology for Learning, was designed for our first year MA students. To develop the conference, we surveyed the students to better understand their knowledge of technology use in the classroom. We discovered that while most students were users of technology, very few used technology in the classroom and very few were familiar with educational approaches and applications for the classroom. The survey was helpful in developing the structure and content for the conference. We then carefully examined which technology based topics and themes were covered in program courses and from there we decided which areas would be best for the conference.

Students expressed they lacked knowledge in, and seemed most interested in, applied uses of technology in educational settings so we decided to host sessions on: blogging, online literacy, assessment, social media in the classroom, gaming, formal and informal learning sights, coding, assistive/adaptive technologies. For a complete list of the sessions and their descriptions click on the website we designed for the conference here:

http://technologyforlearning2016.weebly.com/

Students signed up for the conference via the website and after significant planning, emails and bookings, we were set to go.

The full day conference included: an introduction, 2 one-hour sessions, lunch break, a 3rd one-hour session, student led poster presentations, Q & A and closure. The introductory session led by myself and Heather (co-designers and hosts) set the stage for the day. I introduced the notion of digital citizenship, its themes and local resources and Heather introduced theoretical frameworks for thinking about technology in education. She shared 3 frames: 1) T-Pack 2) Ed Tech Quintet and, 3) SAMR. Each framework was explained and examples were provided. We left students with the suggestion to select one theme from digital citizenship and one framework that resonated with them and to think about them in relation to the 3 sessions there were about to attend. Here are some pictures from the day:

We worked hard to include a variety of presenters, from a variety of settings. Included were the Director of OISE library, a lab school Teacher, Professors from the university, a Teacher from the public school board, and Doctoral students.The images above show some of our amazing presenters.

We provided a lunch where the presenters along with Department Chair Professor Earl Woodruff and Program Chair Professor Rhonda Martinussen gathered to share ideas regarding technology for learning.

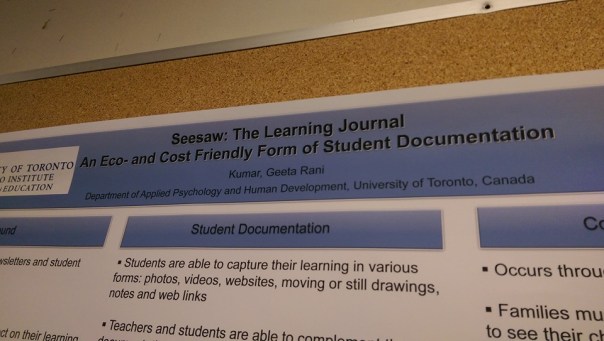

After lunch there was one more set of sessions followed by student-led poster presentations (see images below for student led poster presentations). Students submitted proposals which were reviewed and returned with feedback. The poster presentations provided a wonderful opportunity for students to share their expertise and knowledge in an academic setting. It was a moving and motivational part of the conference.The following 4 images show examples of the student-led poster presentations.

We closed the conference with a Q & A and an unplugging of technology through the fun and fitting picture book “Good night iPad”.

It was a wonderful day. The informal feedback from students has been positive. We plan to send out a post survey about the conference to deepen our understanding of student learning and to improve our own practice in the area of digital literacy teaching. For more information about our conference please feel free to contact us via our blog.

International Literacy Association

The International Literacy Association (ILA) has its annual Conference coming up in Boston in July. An inspiring organization that works to build global capacity in the area of literacy, pre-service and experienced teachers alike have much to gain from learning about ILA and attending the conference.

Check out the website for more information and be inspired!

http://www.literacyworldwide.org/why-literacy

I am inspired by the advocacy piece: http://www.literacyworldwide.org/our-community/educators

From local issues to global issues ILA provides resources for professional development.

Check it out!

Support for Teachers from the Field of Medicine

At last someone has linked the problems of inappropriate use of testing in education with  those of the prestigious profession of medicine. Robert Wachter, Professor of Medicine at UCSF, has written a book titled The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age in which he argues that measurement has gotten out of hand. In a New York Times article “How Measurement Fails Us” (Sunday Review, Jan 17, 2016, p. 5) he states:

those of the prestigious profession of medicine. Robert Wachter, Professor of Medicine at UCSF, has written a book titled The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age in which he argues that measurement has gotten out of hand. In a New York Times article “How Measurement Fails Us” (Sunday Review, Jan 17, 2016, p. 5) he states:

“Two of the most vital industries, health care and education, have become increasingly subjected to metrics and measurements. Of course, we need to hold professionals accountable. But the focus on numbers has gone too far.”

In the article Wachter notes that “burnout rates for doctors top 50 percent” and he says recent research has shown that “the electronic health record was a dominant culprit.” He then draws a parallel with teaching.

“Education is experiencing its own version of measurement fatigue. Educators complain that the focus on student test performance comes at the expense of learning.”

Wachter maintains that what is needed is “thoughtful and limited assessment.” “Measurement cannot go away, but it needs to be scaled back and allowed to mature. We need more targeted measures, ones that have been vetted to ensure that they really matter.” We also need to take account of the harm excessive measurement does. Again he compares the two professions: research has shown that

“In medicine, doctors no longer made eye contact with patients as they clicked away. In education, even parents who favored more testing around Common Core standards worried about the damaging influence of all the exams.”

With this welcome support, we in education need to consider how we can keep measurement within limits and focused on key matters, so it does not undermine our profession. When is measurement useful, and when does it do more harm than good?

Short or Long Form Writing?

There is a lot of enthusiasm today about the potential of short form communication –  tweets, blogs, etc. – to facilitate inquiry and professional development. At the same time, books and long articles continue to be published in huge numbers. Which medium is likely to have greater impact? An obvious response is that we should use both; but when forced to choose (either as reader or writer), which should we opt for? In my (Clive’s) view it depends on the context and how we go about it.

tweets, blogs, etc. – to facilitate inquiry and professional development. At the same time, books and long articles continue to be published in huge numbers. Which medium is likely to have greater impact? An obvious response is that we should use both; but when forced to choose (either as reader or writer), which should we opt for? In my (Clive’s) view it depends on the context and how we go about it.

Teaching is such a complex process that individual tweets or blogs about it may be of little use. However, if they are part of an ongoing conversation (literal or metaphoric) they can be very valuable. It is the same with articles and books: they must respond to the concerns and thinking in the field if they are to be helpful.

Wittgenstein once said (according to Iris Murdoch – NYT, January 24, 2016): “One conversation with a philosopher is as pointless as one piano lesson.” So much for short form communication! But it depends on the context. For a serious pianist, a single interaction with another pianist can have a big impact. And equally, if an academic is willing to dialogue rather than just lecture endlessly about their theory, one conversation can be very helpful.

Whether short or long, communication should as far as possible “keep the conversation going” (to use Rorty’s phrase) so people learn from each other and there is a cumulative effect. We cannot always have an actual conversation, but if we listen to what others are asking and thinking we can make a contribution.

Promoting creativity in teacher education

I (Yiola) have been building in how to embed creativity in classroom practice in my Teacher Education course for a number of years. This year I invited Lina Pugsley, a graduate of the Creativity and Change Leadership Program and Masters of Science in Creativity student from SUNY Buffalo State, to share with us what creativity means and how to teach creatively and teach for creativity through weaving creativity skills into our classroom lessons.

Our class consisted of information sharing about what creativity is and its complexity. I appreciated that we took time to unpack some of the misconceptions (a major one being creativity equals the visual arts) and to solidify some of its characteristics (creativity is problem solving, its innovation, its incubation, its idea generating, its colourful, etc.)

Lina presented us with a number of models and frameworks to think about ways of thinking about, teaching, and embedding creativity into our classroom practice.

Several great resources were shared and a number or creativity scholars introduced. From E. Paul Torrance to Ronald Beghetto, we were inspired!

Once the theoretical and conceptual foundations were laid students in the class began to think more practically about what skills and strategies nurture creativity. This video set our curiosity in motion:

And, in creative fashion students explored, talked about and shared ways of bringing creativity skills into their teaching and lessons. We examined E. Paul Torrance’s 18 thinking skills from his book “Making the Creative Leap Beyond”

Some of the skills:

Be Original

Be Open

Visualize it Rich and Colourfully

Combine and Synthesize

Look at it Another Way

Produce and Consider Many Alternatives

Playfulness and Humour

Highlight the Essence

Make it Swing! Make it Ring!

Be Aware of Emotions

Be Flexible

The energy in the room was high. Students were interested and engaged. They were encouraged to consider their personal teaching philosophy and to make creative thinking a priority in their teaching. It was an inspiring experience. This particular teacher education course looks at methods in education. We explore planning, the learning environment, pedagogies and practices. Creativity, now in the 21st century, is a skill that students must acquire. It is not an innate skill that some are born with while others are not. Everyone has the capacity to develop their creativity skills and as teachers we need to learn how to create classrooms that foster, encourage, and celebrate creative thinking.in I believe the MA students gained a solid sense of what this is about.

For more information on Lina’s focus and work check out here website at:

http://www.keepingcreativityalive.com

A Book Printing Machine at Toronto Library!

The CBC reported that this past weekend the Toronto Reference Library unveiled book printing machine which allows individuals to walk away with store-quality books. As of now, authors can print 10 copies of their books (150 pgs) for $145. A bit pricey in my opinion, but definitely unique with a lot of great potential for students, writers, educators, etc. CBC reports that “What’s new is the ability to self-publish books – whether your own piece of literature, a cook book, dissertation or whatever you choose for a relatively.” The Toronto Reference Library will soon be offering courses on how to best format books for professional looking books.

Read CBC article here:

Neil Gaiman: Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming

I (Clare) read this amazing article from Neil Gaiman. Here is the link to the article: www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming It is a must read for all those interested in literacy — including policy-makers!

It’s important for people to tell you what side they are on and why, and whether they might be biased. A declaration of members’ interests, of a sort. So, I am going to be talking to you about reading. I’m going to tell you that libraries are important. I’m going to suggest that reading fiction, that reading for pleasure, is one of the most important things one can do. I’m going to make an impassioned plea for people to understand what libraries and librarians are, and to preserve both of these things.

It’s important for people to tell you what side they are on and why, and whether they might be biased. A declaration of members’ interests, of a sort. So, I am going to be talking to you about reading. I’m going to tell you that libraries are important. I’m going to suggest that reading fiction, that reading for pleasure, is one of the most important things one can do. I’m going to make an impassioned plea for people to understand what libraries and librarians are, and to preserve both of these things.

And I am biased, obviously and enormously: I’m an author, often an author of fiction. I write for children and for adults. For about 30 years I have been earning my living though my words, mostly by making things up and writing them down. It is obviously in my interest for people to read, for them to read fiction, for libraries and librarians to exist and help foster a love of reading and places in which reading can occur.

So I’m biased as a writer. But I am much, much more biased as a reader. And I am even more biased as a British citizen.

And I’m here giving this talk tonight, under the auspices of the Reading Agency: a charity whose mission is to give everyone an equal chance in life by helping people become confident and enthusiastic readers. Which supports literacy programs, and libraries and individuals and nakedly and wantonly encourages the act of reading. Because, they tell us, everything changes when we read.

And it’s that change, and that act of reading that I’m here to talk about tonight. I want to talk about what reading does. What it’s good for.

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons – a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth – how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn’t read. And certainly couldn’t read for pleasure.

It’s not one to one: you can’t say that a literate society has no criminality. But there are very real correlations.

And I think some of those correlations, the simplest, come from something very simple. Literate people read fiction.

Fiction has two uses. Firstly, it’s a gateway drug to reading. The drive to know what happens next, to want to turn the page, the need to keep going, even if it’s hard, because someone’s in trouble and you have to know how it’s all going to end … that’s a very real drive. And it forces you to learn new words, to think new thoughts, to keep going. To discover that reading per se is pleasurable. Once you learn that, you’re on the road to reading everything. And reading is key. There were noises made briefly, a few years ago, about the idea that we were living in a post-literate world, in which the ability to make sense out of written words was somehow redundant, but those days are gone: words are more important than they ever were: we navigate the world with words, and as the world slips onto the web, we need to follow, to communicate and to comprehend what we are reading. People who cannot understand each other cannot exchange ideas, cannot communicate, and translation programs only go so far.

The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read them.

The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read them.

I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children. Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children’s books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading. I’ve seen it happen over and over; Enid Blyton was declared a bad author, so was RL Stine, so were dozens of others. Comics have been decried as fostering illiteracy.

No such thing as a bad writer…

It’s tosh. It’s snobbery and it’s foolishness. There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn’t hackneyed and worn out to them. This is the first time the child has encountered it. Do not discourage children from reading because you feel they are reading the wrong thing. Fiction you do not like is a route to other books you may prefer. And not everyone has the same taste as you.

Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading: stop them reading what they enjoy, or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like, the 21st-century equivalents of Victorian “improving” literature. You’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and worse, unpleasant.

We need our children to get onto the reading ladder: anything that they enjoy reading will move them up, rung by rung, into literacy. (Also, do not do what this author did when his 11-year-old daughter was into RL Stine, which is to go and get a copy of Stephen King’s Carrie, saying if you liked those you’ll love this! Holly read nothing but safe stories of settlers on prairies for the rest of her teenage years, and still glares at me when Stephen King’s name is mentioned.)

And the second thing fiction does is to build empathy. When you watch TV or see a film, you are looking at things happening to other people. Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.

Empathy is a tool for building people into groups, for allowing us to function as more than self-obsessed individuals.

You’re also finding out something as you read vitally important for making your way in the world. And it’s this:

The world doesn’t have to be like this. Things can be different.

I was in China in 2007, at the first party-approved science fiction and fantasy convention in Chinese history. And at one point I took a top official aside and asked him Why? SF had been disapproved of for a long time. What had changed?

It’s simple, he told me. The Chinese were brilliant at making things if other people brought them the plans. But they did not innovate and they did not invent. They did not imagine. So they sent a delegation to the US, to Apple, to Microsoft, to Google, and they asked the people there who were inventing the future about themselves. And they found that all of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. Discontent is a good thing: discontented people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different.

And while we’re on the subject, I’d like to say a few words about escapism. I hear the term bandied about as if it’s a bad thing. As if “escapist” fiction is a cheap opiate used by the muddled and the foolish and the deluded, and the only fiction that is worthy, for adults or for children, is mimetic fiction, mirroring the worst of the world the reader finds herself in.

If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, why wouldn’t you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with(and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly, during your escape, books can also give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you weapons, give you armour: real things you can take back into your prison. Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

As JRR Tolkien reminded us, the only people who inveigh against escape are jailers.

Tolkien’s illustration of Bilbo’s home, Bag End. Photograph: HarperCollins

Another way to destroy a child’s love of reading, of course, is to make sure there are no books of any kind around. And to give them nowhere to read those books. I was lucky. I had an excellent local library growing up. I had the kind of parents who could be persuaded to drop me off in the library on their way to work in summer holidays, and the kind of librarians who did not mind a small, unaccompanied boy heading back into the children’s library every morning and working his way through the card catalogue, looking for books with ghosts or magic or rockets in them, looking for vampires or detectives or witches or wonders. And when I had finished reading the children’s’ library I began on the adult books.

They were good librarians. They liked books and they liked the books being read. They taught me how to order books from other libraries on inter-library loans. They had no snobbery about anything I read. They just seemed to like that there was this wide-eyed little boy who loved to read, and would talk to me about the books I was reading, they would find me other books in a series, they would help. They treated me as another reader – nothing less or more – which meant they treated me with respect. I was not used to being treated with respect as an eight-year-old.

But libraries are about freedom. Freedom to read, freedom of ideas, freedom of communication. They are about education (which is not a process that finishes the day we leave school or university), about entertainment, about making safe spaces, and about access to information.

I worry that here in the 21st century people misunderstand what libraries are and the purpose of them. If you perceive a library as a shelf of books, it may seem antiquated or outdated in a world in which most, but not all, books in print exist digitally. But that is to miss the point fundamentally.

I think it has to do with nature of information. Information has value, and the right information has enormous value. For all of human history, we have lived in a time of information scarcity, and having the needed information was always important, and always worth something: when to plant crops, where to find things, maps and histories and stories – they were always good for a meal and company. Information was a valuable thing, and those who had it or could obtain it could charge for that service.

In the last few years, we’ve moved from an information-scarce economy to one driven by an information glut. According to Eric Schmidt of Google, every two days now the human race creates as much information as we did from the dawn of civilisation until 2003. That’s about five exobytes of data a day, for those of you keeping score. The challenge becomes, not finding that scarce plant growing in the desert, but finding a specific plant growing in a jungle. We are going to need help navigating that information to find the thing we actually need.

Libraries are places that people go to for information. Books are only the tip of the information iceberg: they are there, and libraries can provide you freely and legally with books. More children are borrowing books from libraries than ever before – books of all kinds: paper and digital and audio. But libraries are also, for example, places that people, who may not have computers, who may not have internet connections, can go online without paying anything: hugely important when the way you find out about jobs, apply for jobs or apply for benefits is increasingly migrating exclusively online. Librarians can help these people navigate that world.

I do not believe that all books will or should migrate onto screens: as Douglas Adams once pointed out to me, more than 20 years before the Kindle turned up, a physical book is like a shark. Sharks are old: there were sharks in the ocean before the dinosaurs. And the reason there are still sharks around is that sharks are better at being sharks than anything else is. Physical books are tough, hard to destroy, bath-resistant, solar-operated, feel good in your hand: they are good at being books, and there will always be a place for them. They belong in libraries, just as libraries have already become places you can go to get access to ebooks, and audiobooks and DVDs and web content.

A library is a place that is a repository of information and gives every citizen equal access to it. That includes health information. And mental health information. It’s a community space. It’s a place of safety, a haven from the world. It’s a place with librarians in it. What the libraries of the future will be like is something we should be imagining now.

Literacy is more important than ever it was, in this world of text and email, a world of written information. We need to read and write, we need global citizens who can read comfortably, comprehend what they are reading, understand nuance, and make themselves understood.

Libraries really are the gates to the future. So it is unfortunate that, round the world, we observe local authorities seizing the opportunity to close libraries as an easy way to save money, without realising that they are stealing from the future to pay for today. They are closing the gates that should be open.

According to a recent study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, England is the “only country where the oldest age group has higher proficiency in both literacy and numeracy than the youngest group, after other factors, such as gender, socio-economic backgrounds and type of occupations are taken into account”.

Or to put it another way, our children and our grandchildren are less literate and less numerate than we are. They are less able to navigate the world, to understand it to solve problems. They can be more easily lied to and misled, will be less able to change the world in which they find themselves, be less employable. All of these things. And as a country, England will fall behind other developed nations because it will lack a skilled workforce.

Books are the way that we communicate with the dead. The way that we learn lessons from those who are no longer with us, that humanity has built on itself, progressed, made knowledge incremental rather than something that has to be relearned, over and over. There are tales that are older than most countries, tales that have long outlasted the cultures and the buildings in which they were first told.

I think we have responsibilities to the future. Responsibilities and obligations to children, to the adults those children will become, to the world they will find themselves inhabiting. All of us – as readers, as writers, as citizens – have obligations. I thought I’d try and spell out some of these obligations here.

I believe we have an obligation to read for pleasure, in private and in public places. If we read for pleasure, if others see us reading, then we learn, we exercise our imaginations. We show others that reading is a good thing.

We have an obligation to support libraries. To use libraries, to encourage others to use libraries, to protest the closure of libraries. If you do not value libraries then you do not value information or culture or wisdom. You are silencing the voices of the past and you are damaging the future.

We have an obligation to read aloud to our children. To read them things they enjoy. To read to them stories we are already tired of. To do the voices, to make it interesting, and not to stop reading to them just because they learn to read to themselves. Use reading-aloud time as bonding time, as time when no phones are being checked, when the distractions of the world are put aside.

We have an obligation to use the language. To push ourselves: to find out what words mean and how to deploy them, to communicate clearly, to say what we mean. We must not to attempt to freeze language, or to pretend it is a dead thing that must be revered, but we should use it as a living thing, that flows, that borrows words, that allows meanings and pronunciations to change with time.

We writers – and especially writers for children, but all writers – have an obligation to our readers: it’s the obligation to write true things, especially important when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were – to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all. We have an obligation not to bore our readers, but to make them need to turn the pages. One of the best cures for a reluctant reader, after all, is a tale they cannot stop themselves from reading. And while we must tell our readers true things and give them weapons and give them armour and pass on whatever wisdom we have gleaned from our short stay on this green world, we have an obligation not to preach, not to lecture, not to force predigested morals and messages down our readers’ throats like adult birds feeding their babies pre-masticated maggots; and we have an obligation never, ever, under any circumstances, to write anything for children that we would not want to read ourselves.

We have an obligation to understand and to acknowledge that as writers for children we are doing important work, because if we mess it up and write dull books that turn children away from reading and from books, we ‘ve lessened our own future and diminished theirs.

We all – adults and children, writers and readers – have an obligation to daydream. We have an obligation to imagine. It is easy to pretend that nobody can change anything, that we are in a world in which society is huge and the individual is less than nothing: an atom in a wall, a grain of rice in a rice field. But the truth is, individuals change their world over and over, individuals make the future, and they do it by imagining that things can be different.

Look around you: I mean it. Pause, for a moment and look around the room that you are in. I’m going to point out something so obvious that it tends to be forgotten. It’s this: that everything you can see, including the walls, was, at some point, imagined. Someone decided it was easier to sit on a chair than on the ground and imagined the chair. Someone had to imagine a way that I could talk to you in London right now without us all getting rained on.This room and the things in it, and all the other things in this building, this city, exist because, over and over and over, people imagined things.

We have an obligation to make things beautiful. Not to leave the world uglier than we found it, not to empty the oceans, not to leave our problems for the next generation. We have an obligation to clean up after ourselves, and not leave our children with a world we’ve shortsightedly messed up, shortchanged, and crippled.

We have an obligation to tell our politicians what we want, to vote against politicians of whatever party who do not understand the value of reading in creating worthwhile citizens, who do not want to act to preserve and protect knowledge and encourage literacy. This is not a matter of party politics. This is a matter of common humanity.

Albert Einstein was asked once how we could make our children intelligent. His reply was both simple and wise. “If you want your children to be intelligent,” he said, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” He understood the value of reading, and of imagining. I hope we can give our children a world in which they will read, and be read to, and imagine, and understand.

- This is an edited version of Neil Gaiman’s lecture for the Reading Agency, delivered on Monday October 14 at the Barbican in London. The Reading Agency’s annual lecture series was initiated in 2012 as a platform for leading writers and thinkers to share original, challenging ideas about reading and libraries.

Your Research Summed Up with EMOJIS!?

Academic writing is often criticized for being unnecessarily complex and as a result inaccessible to most people. In a response to simplify academic writing, there has been a hilarious online movement to tweet your research using only emojis. I decided to try it out. Surprisingly, this task was more difficult than I expected. Below is my final result (I had to use text + emojis). Interestingly, my husband commented the emoji statement helped clarify what the heart of my research is really about. Go figure!!

To Read more about this movement, click here:

http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/10/complex-academic-writing/412255/